This is about rabbits. Not your fluffy Easter Bunnies, but General Woundwort’s thugs from Watership Down, red-in-tooth-and-claw. The bullies who think they have all the answers. As they manically excavate their bunkers and scratch out secret passages, they blindly discard treasures and truth. Things of no value. Flints and buttons and fragments. Priceless incidental things.

Part of my job when working on Cracked Voices was to sift this detritus, to try to find meaning and restore its worth. To glue things back together. Refitting other people’s lost stories. It’s turned me into a sort of historical up-cycler.

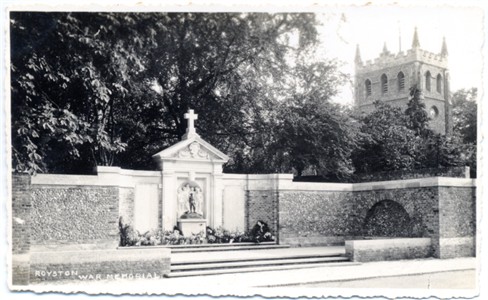

As part of that, I ran a workshop at Royston Arts Festival where we briefly examined one such scrap of overlooked ephemera. It was a postcard produced in a time when new technology and reduced costs meant that local cards like this had become the instant messaging medium of the day (a sort of Edwardian Instagram). It shows a large scale military funeral in Royston in 1914.

The street running up into town from the railway station is lined with people: some in flat caps (railway workers and men from the flour-mill that is just out of the picture), a group of women (maybe from the nearby alms houses, reserved for widows) and, on the opposite side of the street, one or two middle-class men, distinct in their straw boaters – all watching the soldiers with their reversed rifles, followed closely by the military band, the coffin (wheeled on a bier which can still be seen in Royston Museum) and the two carriages of official mourners. This was no silent affair. The march – a piece of music by Handel – lifted the onlookers hearts. It was the same patriotic piece as had been played at Admiral Nelson’s funeral.

My immediate question was, ‘Who was this man?’ Lots of people died in World War 1, why was he so special?

A search through the local paper turned up this unexpected headline:

Albert Reeve was a 25 year old Sergeant in the Territorial Force (the volunteer reserves of the British Army) but he had died doing his day job, maintaining track on the railway just outside Letchworth. He had been highly respected by his comrades in the TF and fellow railway workers and there may have been some disquiet at the way that Reeve’s body had been handled – the inquest into his death commented that a mortuary should be built in Letchworth as Reeve’s corpse had had to be kept in a stable. But that wasn’t solely it.

It was the date. Friday 17 July 1914.

Britain was not yet at war but in the grip of the ‘July Crisis’. Arch-Duke Ferdinand had been assassinated on 28 June but it would be another seventeen days before war was declared on Germany. That July, people knew war was coming and were scared.

In Royston a show of pomp would prepare the way for the great sacrifice. As Rev. J. Harrison declared at the graveside, ‘They had come there to pay a last tribute to one who was good comrade, a good son, and a good fellow. To them it seemed that his end had been untimely, but when men were on active service, they carried their lives in their hands, and must be prepared for that great change. He wanted them to remember that they were all enlisted in one great army, which was captained by Christ Himself. What was the secret by which they might live and be ready? Their secret was faith in the Captain Himself, the blessed Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ.’

So Reeve’s funeral was used as a rallying cry to all the good sons. Soon Britain would need them all. The railway-worker had been mythologised. He wasn’t special at all, but his death had been invested with meaning. It was to serve a function. This was less Instagram and more Fox News.

Have a go…

The context is the story…and, thanks to the rapid advance in cataloguing and searchable databases, context is easier to establish than ever before.

Why don’t you find yourself a story by downloading the image of an old postcard from e-bay and then looking into its context? Remember, if it interests you, it’ll probably interest someone else.

There’s all sorts of useful research tools out there:

Newspapers: British Newspaper Archive (free at Hertfordshire Libraries) [includes Herts & Cambs Reporter (Royston Crow) 1878-1910] or National Library of Wales (Welsh papers often reprinted articles from England): http://newspapers.library.wales/ This is free to access anywhere.

Maps: OldMapsOnline.org Free

Trade directories: University of Leicester, Special Collections Online Free

Local history section in your local Library

Research sessions run fairly regularly in local museums and archives

Family history: Findyourpast & Ancestry.com (free at Hertfordshire Libraries)

Second-hand books: Bookfinder.com

Go on, save a fragment from General Woundwort’s thugs and up-cycle the past…