Revolution…

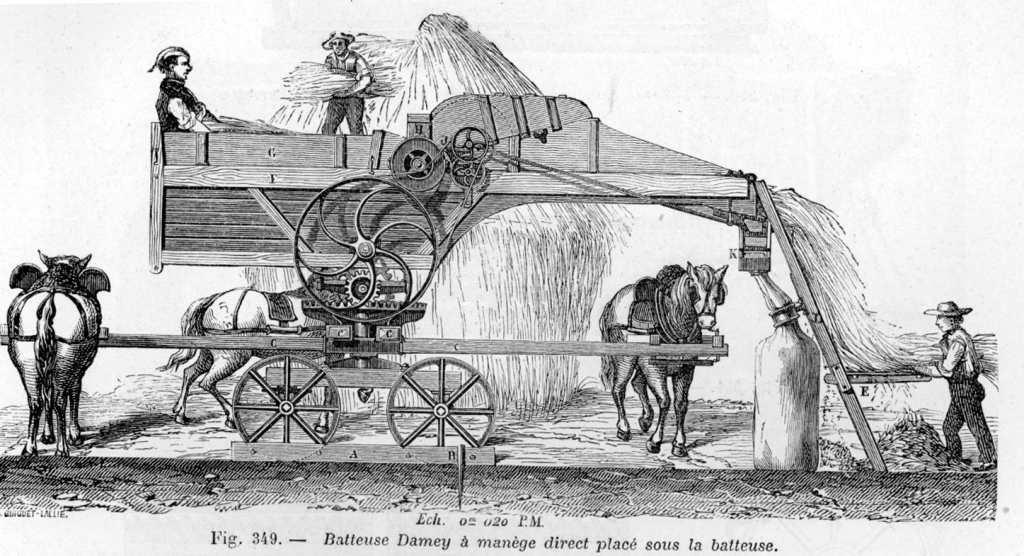

On 28 August 1830 angry men smashed up a threshing machine in East Kent.

It was not unknown for a disgruntled farm worker – worse for drink and in the gloom of night – to set fire to a farmer’s stacks of hay or straw to get his own back for some slight, but this was unprecedented.

The destruction of the machine was not the result of one man’s grudge, it was a concerted action: the first sign of something far more dangerous to the government.

Three years of poor harvests, enclosure and the mechanisation of threshing (which had always been the main source of work in the winter) had left many agricultural labourers without a job.

Farmers were only committing to short-term contracts which paid lower wages and, when those were not renewed, workers were forced to turn to the parish for handouts, only to find that ‘relief’ was also being cut.

In the coming months resentment and rioting would spread rapidly throughout the country.

The papers carried news of revolution in France and revolts in Belgium and Poland, and some wondered, ‘Why not here?’

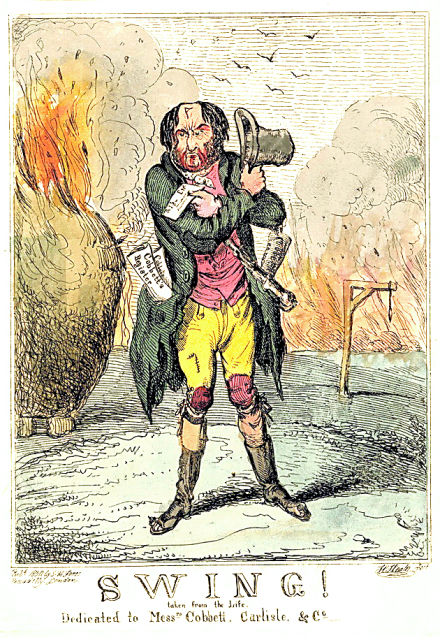

Captain Swing

Trade Unionism was still in its infancy and there was no national organisation to represent the farm labourers’ interests.

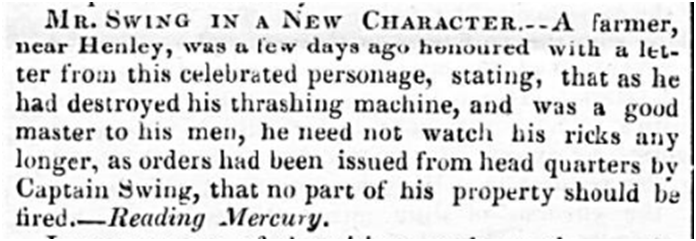

Consequently, the disparate protests flaring up around the country were connected only by a deep-rooted anger, travelling agitators and the non-existent ‘Captain Swing’ (‘Swing’ being the favoured nom de plume when sending otherwise anonymous letters designed to intimidate farmers).

Ashwell in ashes

At Croydon, near Royston, the parish overseer (Mr. Fairclough) saw his threshing machine destroyed.

At Guilden Morden Mr. Butterfield’s stacks burnt, costing him £1,500 and many more fires were set at Wimpole and Ashwell.

At Bassingbourn it was reported that most of the farm homesteads had been destroyed, while at Meldreth John Burr (the churchwarden) wrote that workers had threatened farmers that they must ‘Keep up the price of labour or there will be always be cause to fear.’

Worries at Wimpole

By 15 November things had become so serious that Sir Robert Peel (who within the week would lose his own job as Home Secretary ) admitted to Parliament that ‘four or five hours every day of my life are spent in endeavouring to discover the perpetrators of these atrocious crimes.’

Peel confirmed that, rather than just prosecuting offenders after the event, if local magistrates thought a disturbance was imminent they had the power to ‘call on any number of householders to act as special constables’ and quell the uprising.

At Wimpole, the 73 year-old 3rd Earl of Hardwicke was deeply concerned. As Lord Lieutenant of Cambridgeshire, he was one of those tasked with suppressing any local protests.

On 2 December he wrote to Viscount Melbourn (Peel’s successor) requesting inquiries into the state of the labouring poor and how best to combat ‘combinations’ (i.e. labourers acting together as proto-Trade Unions).

Reluctant Royston

Seven hundred townsfolk from Cambridge had already volunteered as Special Constables but, Hardwicke informed Melbourn, he had found the men of Royston reluctant to offer their services when they met on 1 December .

The townsfolk were concerned that, if they took the necessary oath, ‘they would be marked Men and objects of Vengeance to the ill affected.’

Rather than force the issue, Hardwicke deferred to their fears and instead ‘got them to sign a paper committing them to serve when called upon.’

The Earl was certain of one thing: the local fires were ‘not the work of the peasantry themselves, but of persons who are strangers to, and unconnected with, the neighbourhood.’

A resident of Wisbech agreed and proposed his own solution to the Home Secretary: it was impracticable to restrict movement but all unknown visitors to a district must be ’required to give an account of themselves.’ Such action would ‘affect the innocent and the guilty’, but he was sure that folk would concede the intrusion was a price worth paying.

Stranger danger

On the very day Hardwicke met with the townsfolk of Royston, a stranger had stopped at the Royal Oak in Litlington. In the bar that evening this well-dressed curly-haired man listened to how the locals were planning to burn farmer Moss’s stacks and urged them instead to ‘knock him on the head.’

The stranger boasted of how he had travelled through Kent, Sussex, Norfolk, Suffolk and Yorkshire, all counties where numerous fires had been set. If the government did not concede, he claimed, a revolution would follow the current sitting of parliament. The labourers would be safe for he was certain that ‘the soldiers would not fight against the People.’

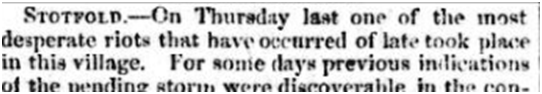

In the morning he set off towards Baldock, passing near to Stotfold where, The Times reported, ‘one of the most desperate riots’ broke out.’ (It appears the stranger’s presence was merely coincidental as the rioters had first gathered the previous night demanding that the parish overseer be removed).

Stotfold’s ‘most desperate’ riot

According to the Cambridge Chronicle, the workers who reassembled next morning had an additional demand: every man should receive 2 shillings per day for his work. But where was the money to pay for the increase to come from? The local farmers had countered. ‘Thomas Cooper, replied…2s a day they would have!’ Another man shouted. ‘”Damn their eyes! Let’s begin to pitch into them!”‘ and a fight broke out.

The Times continued, ‘The infuriated assembly (from 100 to 200 in number) … proceeded to acts of violence, and went through the village demanding bread from the bakers, beer from the publicans, and money from the inhabitants generally.’

That evening stubble was collected from the fields and set alight and the workers gave out that their demands must be met by the following Saturday or more trouble would follow.

In response, Reverend John Lafont (rector of Hinxworth) took it on himself to ride over to Wrest Park to warn the Lord Lieutenant of Bedfordshire but, finding Lord Grantham absent, concerted with others including John George Fordham of Odsey and Royston to raise 150 of Grantham’s men from Silsoe and 300 men with dogs from Stotfold to suppress the riot.

Ten of the ringleaders were arrested but Lafont reported back that ‘all the threshing machines hereabouts are pulled down by their owners – hence you see the labourers have succeeded… added to which the farmers have been so far intimidated as to raise their wages generally.’

On Monday 6 December the rector travelled onto Therfield and Kelshall and found the villages ‘perfectly quiet.’

Foul play at Fowlmere

Towards the end of that month it was reported that labourers at Fowlmere had ‘combined in a determination to prevent all persons doing any work in the Parish until the wages were raised and which they carried into execution with considerable violence to some of those who were willing to work.’

On 22 December Henry Hawkins (a Justice of the Peace who lived at the Priory in Royston) set out with a warrant and thirty special constables he had recruited from the townsfolk.

In a letter to the Home Secretary, the Royston solicitors Nash and Wedd reported, ‘About 100 of the Labourers were assembled together armed with large sticks and refused to give up the persons named in the warrant; upon which a contest ensued which ended in the prisoners being taken, but not until some severe blows had been received by individuals on both sides. One of the Labourers was reported to be dangerously wounded but we understand he is recovering.’

The solicitors humbly enquired if the crown would pay for the prosecutions, while those taken were imprisoned in Cambridge.

Consequences

Following the Swing riots, nearly 2,000 criminal cases were tried, 19 people executed, more than 500 transported (including two who had been involved in the Stotfold riot) and more than 600 imprisoned.

Nationally, discontent would rumble on for years and it would soon resurface in Royston.

Read more in Revolting Royston (2): Royston’s Bastille.

POSTSCRIPT

In his book (Fragments of Two Centuries), the then editor of the Royston Crow newspaper, Alfred Kingston, claimed that the ornamental staves issued to the Special Constables by Hardwicke still occasionally turned up ‘amongst local curiosities’ as late as 1906.

Farmer Moss in Litlington seems never to have regained the respect of his workers. In 1844 he awoke to find three of his sheep lying dead in their fold, their severed tongues placed carefully next to them.

Five years later, a fire set in his stack yard spread to ‘two barns filled with corn, and nearly the whole of the farm buildings were destroyed.’ The Hertford Mercury & Reformer reported, ‘There were a great number of labourers present, most of whom refused to work and conducted themselves in a most riotous and disgraceful manner.’

SOURCES

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Fragments of Two Centuries, by Alfred Kingston

Incendiaries In The Country – Hansard – UK Parliament

The Stotfold Riot by Mr Bert Hyde – Digitised Resources – The Virtual Library (culturalservices.net)

The National Archives (TNA), Home Office correspondence, HO 52/6/173-174; HO 52/6/176-177; HO 52/7/208

Bedfordshire Archive, L 30/18/27/1-2

The Times, 6 December 1830

The Cambridge Chronicle, 11 March 1831

The Hertford Mercury & Reformer, 27 April 1844, 10 February 1849

One comment