In 1533 England is gripped by terrible convulsions following Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn and the break from Rome. Robert Dalyvell is imprisoned, suspected of spying. When he is released, he is missing his ears. Just three years on in 1536 Anne has lost not her ears but her head, and Dalyvell will soon come under suspicion once more.

Robert Dalyvell’s

cunning craft & prophecy

England is not a safe place to live. The Reformation is in its infancy and might yet be snuffed out. Following a bad harvest, protests erupt in the north of England, primarily in York (Cardinal Wolsey’s former stronghold) and Lincolnshire. The protestors believe the king is being misled by his council and that their ‘Pilgrimage of Grace’ will save the country. The ‘pilgrims’ are demanding the reestablishment of the Catholic Church, the restoration of the monasteries and the removal of commoners (such as Thomas Cromwell) from the King’s council. Pontefract Castle is besieged and Henry dispatches an army to deal with the ‘pilgrims’. Following the suppression of the rebellion, another breaks out in January 1537 but is also crushed. More than 200 protestors are put to death.

England remains vulnerable to both internal Catholic coup and foreign invasion while Henry lacks an heir. Though Jane Seymour is pregnant, as the King has declared both his daughters illegitimate, the succession is not yet guaranteed. To make matters worse, his nephew in Scotland (James V) has revived the military pact known as the ‘Auld Alliance’ and wed the daughter of Francis I of France. (A move so worrying to Henry that when James refuses to break with Rome just five years later, Henry launches an incursion and initiates Scotland’s ‘rough wooing’, aka the eight-years war.)

Henry has good grounds to be worried. The European Catholic powers are conspiring to depose England’s heretic king and replace him with James. To counter this, Henry’s council orders that the defences of Calais, Carlisle and Berwick be bolstered and sends letters to all local Justices of the Peace telling them to be especially vigilant for anyone spreading sedition.

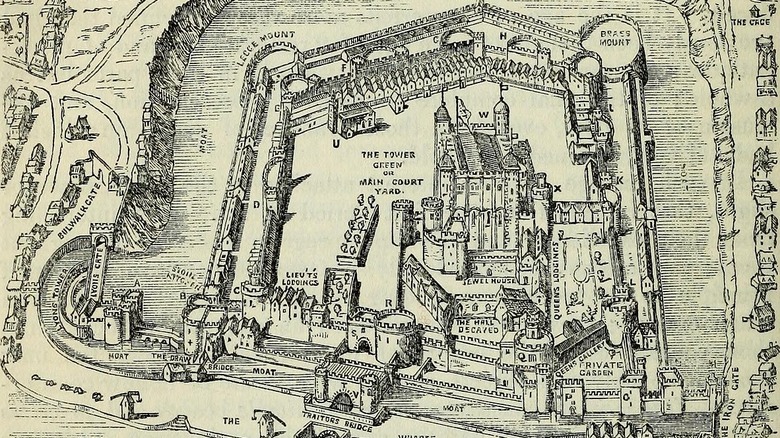

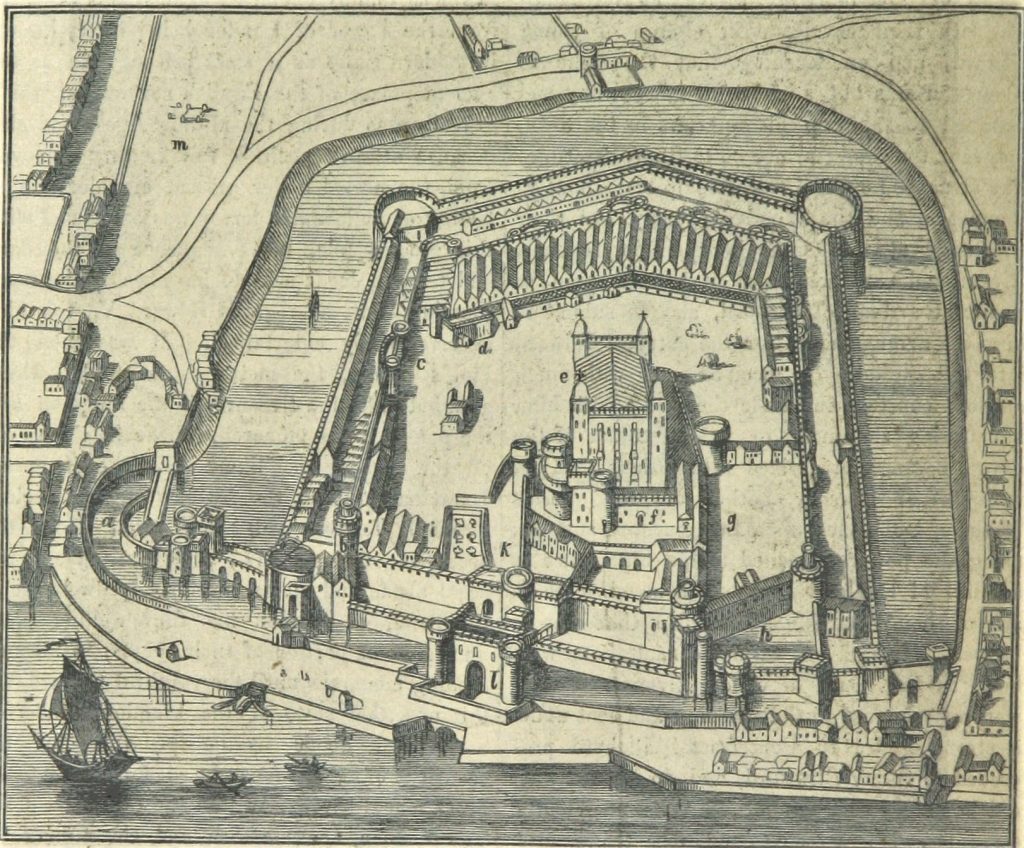

In Royston, Robert Dalyvell opens his mouth once too often and soon finds himself strapped onto the rack in a dungeon at the Tower of London on 12 June 1537. First sight of the terrifying contraption often inspires prisoners to say whatever the Lieutenant of the Tower wants, but not this man.

Dalyvell has influential relations in the north – his uncle is none other than Sir John Delaval, the High Sheriff of Northumberland. Quite how Robert has been taken in Royston – just a day’s ride from London on the Old North Road – is unclear. Perhaps he had been just passing through, though his initial ‘confession’, taken in the town on 11 June, clearly states that he is ‘of Royston’ (it’s possible this is a slip of the scribe’s pen).

Under torture in the Tower, Robert reveals that he visited Edinburgh the previous summer where he stayed eight weeks ‘to learn cunning in the craft of a saddler’. During that trip ‘divers Scotchmen’ had told him that ‘their King [James] should be crowned king of England in London before Midsummer day three years or a month after.’ Reading to him out of a book of divination, they claimed the event had all been prophesied by Merlin himself.

He had also visited his northern relations and found work for three weeks at Chester-le-Street. There, some Scots had told him that James V ‘was most worthy to be king of England, being next of blood’. York, the city which that autumn would become a hotbed of the ‘Pilgrimage of Grace’, was another of the main stops on the North Road. For two whole weeks Dalyvell chose to ply his trade within its walls (though whether that trade was saddlery remains open to question).

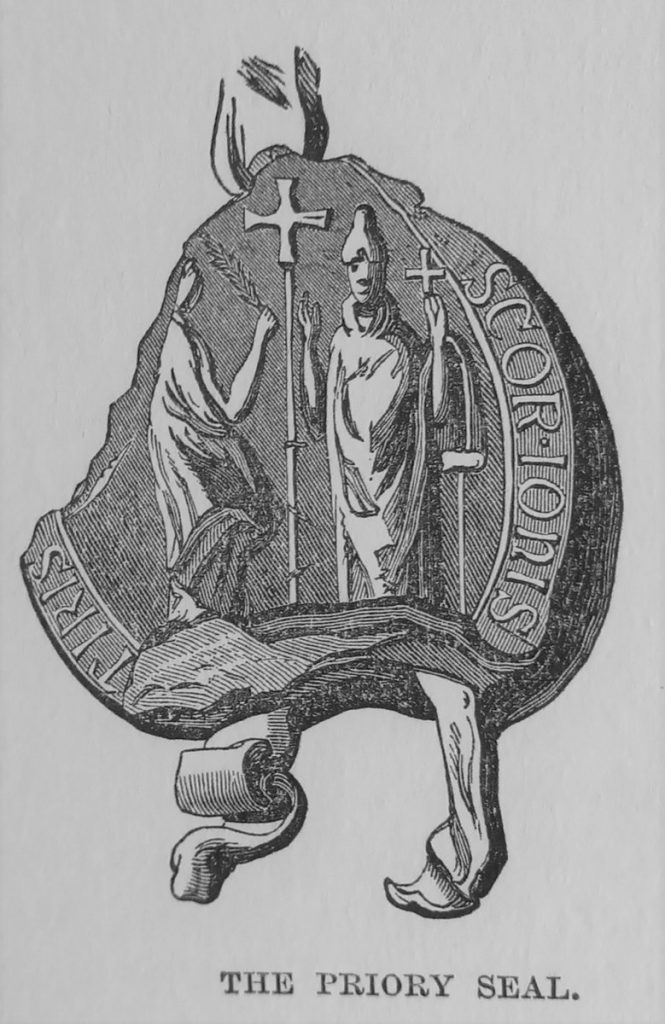

How long Dalyvell had been in Royston in 1537 is not known, but on the first Monday in June he had a quiet chat with a gentleman’s servant in the stables of the Greyhound Inn. Just seven weeks earlier the town’s priory had been dissolved, leaving its six canons with little to support themselves, though the prior had been allowed an annual pension. The priory had dominated day-to-day life for more than 350 years and the townsfolk must have worried what their future might now be.

(Source: A History of Royston, Alfred Kingston (1906))

Undoubtedly, discontented mutterings about the dissolution encouraged Dalyvell to let slip the Scots’ prophecy. In those fractious times it was not a wise move, and on 11 June he found himself in front of a panel comprising of four leading gentlemen of the town (‘John Martyn, Edw. Annesley, Ric. Chambre, and Wm. Chambre’) and three from York (‘Peter Robynson, Ric. Gollthorpe, and Tristram Teshe’).

In their record of his examination they noted Dalyvell’s prediction that, if the king did not amend his ways, he would be dead within a month of the Feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist (25 June) the following year (1538). In addition, all but one of Henry’s lords would perish (in Dalyvell’s words, a single horse worth 10 shillings ‘shall be able to bear all the noble blood of England’). An angel had apparently told him ‘to show your prince that the Scots would never be true to him.’

It was all very perplexing. Dalyvell’s claims were far too damning for the local gentry to investigate further, so that same day they transported him to the capital and handed him over to the Lieutenant of the Tower of London, Edmund Walsingham, for interrogation.

(Source: The National and Domestic History of England, Vol.2, (1878) W H S Aubrey)

Henry’s chief counsellor Thomas Cromwell had already prepared a memorandum instructing Walsingham on the questions he was to put to the prisoner:

- To ask him when he was last in Scotland, and why he went thither?

- How long, and with whom he dwelled there?

- What he heard of the King and realm, and from whom?

- With whom he spake and where he stayed in the North on his journey?

- Whether he has heard of any prophecies?

- If any religious person has read him any prophecies?

- To how many people he has told the matters contained in the two articles.

- What he said to the Scotchman who told him of the effect of the matter contained in the two articles.

- How long ago and how often the angel appeared to him?

If Dalyvell was a spy or agent provocateur, he was better at his job than Walsingham. (Of course, he may just have been deluded.) Dalyvell had no memory for the names of the people who had revealed the prophecy but could affirm that they had not been priests and that the angel had appeared to him on two occasions around Palm Sunday. Other than that, all he really revealed was the extent of his travels.

In his report dated 12 July, Walsingham noted, ‘I brought him to the rack and there strained him, using such circumstances as my poor wit would extend to; but more cannot I get of him than this. Yesternight I proved him at his first coming, and about 8 of the clock again, and in the morning after again, by fair means and threatenings.’

Dalyvell’s suffering did little more than shine a light on the all-pervasive paranoia holding England in its thrall.

That October, complications in childbirth felled Jane Seymour just 12 days after delivering Henry a male heir. Cromwell’s next choice of a bride for the king, Anne of Cleaves, proved a disaster for which he paid with his head.

Concerned at destabilizing rumours still swirling throughout the country, in 1542 Henry persuaded parliament to pass ‘An Act concerning false Prophecies upon Declaration of Names, Arms or Badges’ which made the writing, printing, singing or retelling of any false prophesy concerning the king or his nobles punishable by forfeiture and death.

This Act, of course, gave no hint as to how to determine whether a prophecy was false and Henry VIII made sure that judgment would remain his alone. Such was the privilege and curse of kingship.

© Graham Palmer, June 2022

Sources

- A History of Royston, Alfred Kingston (1906), p.60-61

- The Book of Prisoners, quoted at Camelot International: Britain’s Heritage and History

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 12 Part 2, June-December 1537, ed. James Gairdner (London, 1891), p. 25-42

- 1541-2 (33 Hen. 8 c. 14) An Act concerning false Prophecies upon Declaration of Names, Arms or Badges. Printed in The statutes of the realm v.3, p.850 (1817, reprinted 1963)