Since the unsettling events in London of the previous week, Royston’s ever-alert exciseman, Jeremiah Berry, had been on the look out for strangers.

Had it not been for his Scotish burr, Patrick MacGregor (alias Campbell/McAlpine) might well have slipped past Berry undetected. It was not to be.

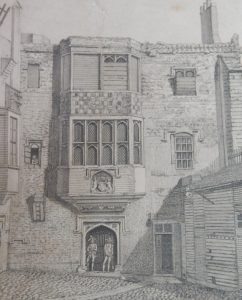

On 22 May 1743 the exciseman bundled his prize to Cambridge where the ramshackle gatehouse of the old castle still acted as the local jail.

Taming the beast

In England the Scottish Highlander was known to be a dangerous beast, best housed with the lions in the Tower of London.

A rare sighting of one of these exotic plaid-wearing, bare-arsed foreigners inspired a certain frisson.

They looked different, sounded different and could not be trusted. They had already launched two violent missions to dethrone the King and restore the House of Stuart.

Without maps or the benefit of satellite images, hunting down the insurgents in the inaccessible mountains of Scotland was the 18th century equivalent of scouring the tribal areas of Pakistan for al-Qaeda.

(one of the Pennicuick drawings)

General Wade had been given the unenviable task of taming the country, mapping its ungovernable tracts and disarming its inhabitants.

First came a massive building programme. The Great Glen was fortified and the forts linked by new military roads.

Next, six ‘Highland Independent Companies’ were raised to suppress the dissidents. Each of these units was to patrol the area where its men – all high-ranking Highlanders – had grown up. Their officers knew every cave and overhang where guns or rebels might be concealed.

While everybody else (apart from the odd cattle drover) was required to surrender their weapons, these men alone were allowed to hold on to theirs. It was a grand opportunity for a would-be insurgent to hide in plain sight while enjoying the benefits of a military training.

Each carried the traditional claymore (a basket-hilted broadsword), dirk (dagger) and targe (circular shield), and the officers carried their own pistols, supplemented by government-issue flintlocks and bayonets.

As far as uniform went, the men remained virtually indistinguishable from civilians apart from the black ribbon (known as a cockade) which they wore in the bonnet to demonstrate their loyalty to the (current) Royal House of Hanover.

What’s in a name?

In the Highlands, landlords had traditionally paid privately contracted Watches (gangs of former – or possibly, current –

cattle-raiders) to ensure that when any of their beasts were stolen they would be returned safely. For this service the landlords paid the local Watch an annual fee known as ‘blackmail’ (a new word for a time-old custom).

Now, the landlords were keen that the new security arrangements should put an end the protection racket (and save themselves some money along the way).

The Independent Companies would take on the responsibilities of the various watches. In turn the rookie soldiers became known locally as ‘Am Freciadan Dubh’, the Black Watch.

War with Spain came in 1739 and heralded a UK-wide defence review which saw the Independent Companies put on a more formal footing. Alongside the six Companies already in existence, four new ones were raised and amalgamated into a new regiment officially known as the 43rd Regiment of Foot (or Highland Regiment), though the locals still knew them as the Black Watch.

More reputable than gold

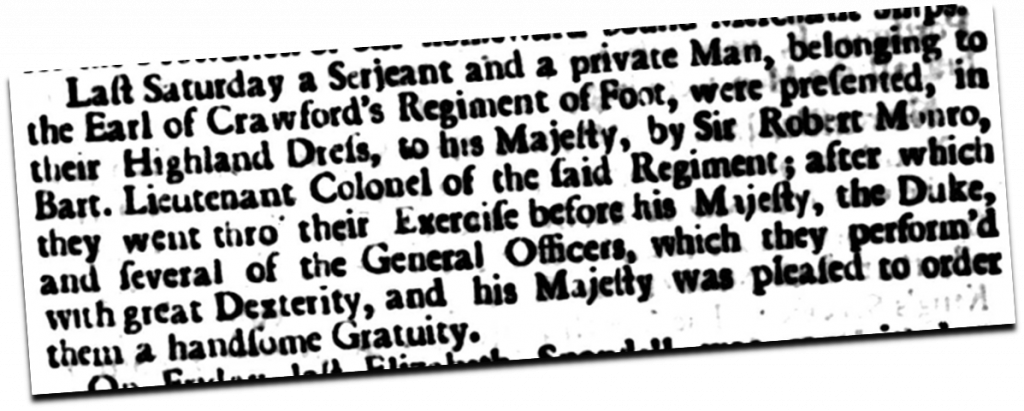

The new regiment’s Colonel was keen to advertise the men’s abilities and selected three of the fittest (and most handsome) to demonstrate their military prowess to the King. One man fell ill on the journey to London, so on 5 January 1740 just two presented themselves at Court. After a magnificent display, George II declared he was delighted with the show and gave them each a guinea.

Is cliùtach an onair na ‘n t-òir, goes the Gaelic proverb: honour is more reputable than gold. Insulted, or perhaps as a not-so subtle nod that their allegiance lay elsewhere, the Highlanders handed the King’s tip to the palace porter as they left.

War in Europe

By the early spring of 1743 the military situation in Europe had become critical and the British top-brass needed every man they could muster.

However, the men of the Highland Regiment had always thought of themselves as a Watch, whose sole raison d’être was the policing of Scotland. They were special, set apart from the rest of the British Army.

After all, they did not wear the standard uniform of a foot regiment but rather the local plaid and Highland bonnet, they did not carry the standard infantry sword but rather the claymore, while many of the regiment recalled how they had been raised as local Independent Companies.

In the past they had been reviewed by Wade and when an inspection was ordered at Musselburgh, just outside Edinburgh, they thought nothing of it, not knowing that their commanders had secret orders to march them to London from where they would be dispatched overseas.

In a letter, the politician and novelist Horace Walpole noted two months later,

“…their lieutenant-colonel, before their leaving Scotland, asked some of the Ministry, ‘But suppose there should be any rebellion in Scotland, what should we do for [lack of] these eight hundred men?’

It was answered, ‘Why, there would be eight hundred fewer rebels there.’”

In the politicians’ eyes these half-tamed barbarians from north of the border remained untrustworthy and clearly would serve better as cannon fodder on the continent.

The 400-mile trudge

At Musselburgh the men were told the review had been moved south and would be in the English town of Berwick. There, they were informed that they were to have the great honour of the King himself reviewing the regiment in London.

For most this was the first time the mainly Gaelic-speaking soldiers had left their native glens. The further they marched into a country where they did not understand the language, customs or dress, the greater the confusion and anxiety they must have felt.

To add to their woes, they were expected to collect from the jails along their route any deserters from regiments serving overseas – men who told their own horror stories to those soldiers who could understand them – and escort them under guard to London’s Savoy military prison.

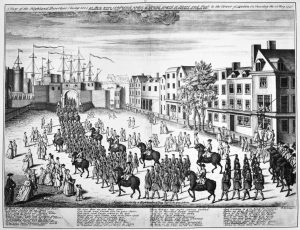

At Newcastle, 1,500 townsfolk turned out to gawp as the savages passed by. At Royston, the regiment split to head for different encampments on the outskirts of London where one witness noted, “When the Highlanders walk’d the streets here…there was more staring at them than ever was seen at the Morocco embassador’s attendance or even the Indian chiefs.”

The last straw

On reaching London the men were informed that the King had sailed to the Continent to lead his troops. Instead, General Wade reviewed them on 14 May in front of thousands of spectators and they learned that they too were being shipped overseas. On Tuesday 17 May they were told the first contingent would ship out in the morning. Rumours circulated that they were being sent to the West Indies (a punishment previously meted out to rebels). Faced with this humiliation, they snapped. At midnight more than 100 men of the Highland Regiment gathered in the darkness of Finchley Common and resolved to head home.

When challenged by Captain John Munroe and Lieutenant Malcolm Fraser, they raised their bayonets, ‘threatening to kill the officers if they did not leave.’

Hunted down

A second group of between 60 and 70 men headed out shortly afterwards, heading for St Albans, while the first marched in formation north and, when night fell again, sought out small woods to offer them cover.

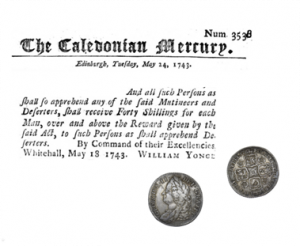

In the King’s absence, next day the Lord Justices met in London and authorised payment of 40 shillings (in addition to the usual reward for apprehending deserters) to anyone who could catch one of the mutineers.

On the evening of 21 May Major Creed finally tracked the larger party down to Lady Wood near Oundle (Northamptonshire) and convinced them that they were surrounded.

The mutineers, however, refused to lay down their arms without the guarantee of a pardon. The Major had some sympathy for the men but was not authorised to give any kind of guarantee. When General Blakeney arrived two days later he refused to grant any terms. Outnumbered and faced with the prospect of opening fire on fellow soldiers, the mutineers surrendered and were marched back to London to be imprisoned in the Tower.

Those of the regiment who had not joined the ill-fated mutiny had already shipped to the Continent.

The Court Martial

The men’s trials took place in the Tower and lasted a full week from 8 to 15 June.

Their testimony was virtually identical (though much of it had to be given through an interpreter).

Each claimed the mutiny had no leader, admitted he had sworn the oath of allegiance to the King and had had the Articles of War read to him. Each had duly received his pay and clothing and had no complaint against any of his officers. So why had they mutinied?

Those few that did risk grumbling complained that they had been tricked into marching to London, they had been given no time to put their affairs in order and that they feared being shipped to the disease-ridden Caribbean. They were due pay, their clothing and shoes were deficient (especially as their replacement plaids were of poor quality), and they had to supply their own swords.

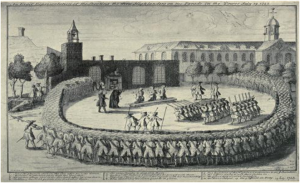

(contemporary French print)

James MacFarland (through an interpreter):

We had no leader or chief, every one was his own master. As the regiment was raised in Scotland, we would go nowhere else.

John Farquharson:

We heard we were to be sent to the West Indies, where we would not live above a week for the severity of the climate.

Thomas Stewart:

I’d been a soldier 16 years in one of the independent companies before it was regimented and have no ill-will against the officers. I went off with the men, with my arms and accoutrements; and expected the whole Regiment would follow, but when it was found they did not, we repented of what we had done.

Later, it was to be asserted that a stranger had visited them in the Tower before the Court Martial. He had advised them not to make any complaint about their officers, saying that if they did it would be held against them. An officer had also given them the same advice. Both men had promised that, as long as the mutineers kept mum, they would escape all punishment.

Punishment

The sentence for mutiny was death. Fortunately, as the man who had been caught in Royston had deserted before the men had mutinied, he would receive a lesser sentence. Executing over a hundred men was impracticable and in any case they were needed to fight overseas so the Lord Justices relented.

Only three would die and the rest would watch them. The Governor of the Tower and the officiating minister each wrote separate accounts of the execution, which I have edited together here.

Scapegoats

The three men chosen as scapegoats were Corporal Samuel MacPherson, his cousin Malcolm (also a corporal) and Private Farquhar Shaw.

The MacPhersons where both from Laggan. Twenty-nine year-old Samuel was son to a landed laird and had studied under a lawyer before joining the Independent Companies six years earlier. He had been positively identified by the officers who had challenged the mutineers on Finchley Common as the mutiny’s ringleader.

A year older, Malcolm had been part of Lovat’s Independent Company and had been one of the men who negotiated the men’s surrender at Lady Wood.

Farquhar Shaw (a 35 year-old from Rothiemurchus in Strathspey) was a drover and been forced to enlist out of poverty. He was accused of struggling with a sergeant during the mutiny.

The severity of the climate

The 100-odd men who witnessed the executions were soon split up, drafted into other regiments and sent overseas, some to Minorca and Gibraltar, some to Georgia and, yes, some to the Leeward Islands in the dreaded West Indies.

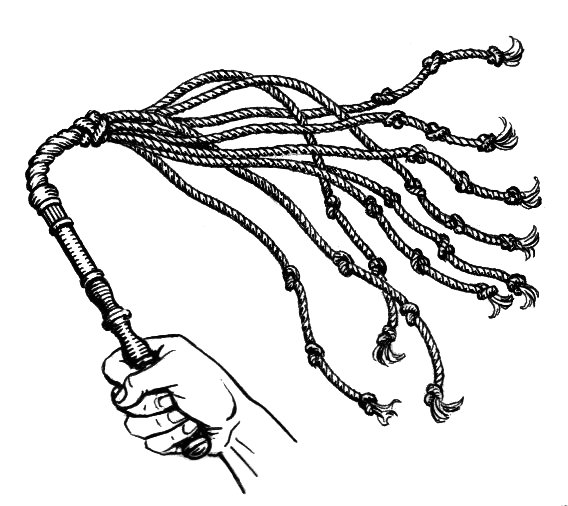

And Patrick MacGregor, the man from Royston? As a mere deserter, he was sentenced to receive one thousand lashes of the cat-of-nine-tails.

Not wanting to kill him by giving them all in one go, the Court Martial ordered that 200 lashes should be administered over five different occasions, allowing his back just enough time to heal over between sessions.

(Image: Wiktionary)

Patrick did not appeal the sentence but sent a petition to the Secretary at War requesting he not be sent to Georgia and on 12 July the Lord Justices suggested to the King that ‘instead of the corporal punishment, he may be draughted to be sent to Gibraltar or Minorca.’

On 4 August the Secretary at War wrote that ‘no determination has yet been made’ about his case.

Preparations had been made that he would join Offarell’s regiment and ship to Minorca but on 2 September the Colonel was informed that he should sell the sword that had been delivered to him for Patrick’s use as Patrick would not be needing it.

At the end of October the King finally agreed to discharge Patrick from the Tower on the condition he re-enlist to serve in Gibraltar or Port Mahon (Minorca). It seems he was never whipped.

What happened next and why the dithering is unknown.

Meanwhile…

In Royston, Jeremiah Berry was instructed to contact London to collect his reward of 40sh.

Locally, the matter of who should bear the cost of catching Patrick and getting him to Cambridge had become a hot potato.

Eventually the Deputy Secretary at War was to concede that ‘tho’ the parish or hundred ou[gh]t to bear the expence, if any, in carrying deserters to prison, you may draw upon me at the War Office for one pound six shillings, the charge the constable was at on acco[un]t of Patrick McGregor.’

Back at the Tower

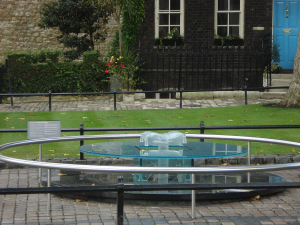

In September 2006 a ‘Memorial to the Executed’ was unveiled in the Tower of London. On it the three executed mutineers are remembered alongside Catherine Howard and Anne Boleyn.

at the Tower of London

(Image: Wikipedia)

And finally…

Sixty two years later, the Black Watch was once again visiting Royston. One thousand soldiers were billeted on a town with a population of roughly thirteen hundred so it would, to say the least, be a cosy few nights.

From the account left to us by Sergeant Rowland Cameron of the regiment, it is generally understood that the men were first awarded red hackles to wear in the bonnets when they assembled on Therfield Heath on 4 June 1795. The honour of wearing these distinctive red feathers was believed to have been given as a reward for their extraordinary actions at Guildermalson.

“After firing 3 rounds in honour of HM George 3rd’s birthday, a box containing the feathers arrived on the Common.” They “placed the Feathers in their bonnets and marched into Royston, and…were paid the arrears due for eighteen months, with a caution to keep close to their billets and be regular.”

With that amount of money in their sporans, it must have been a rowdy night in Royston’s Inns!

However, Cameron was elderly when he gave his account. General James Stirling, the man who was to command the Black Watch just nine years on from the muster on the Heath, noted how the hackle had first been worn during the American War of Independence. The distribution of the feathers in Royston was neither the first nor the last time it would occur – just a notable occasion – and it was not until 20 August 1822 that the regiment was awarded the exclusive right to wear them.

Sources

- A Short Account of the Highland Regiment, (1743)

- The Behaviour and Character of Samuel Macpherson, Malcolm Macpherson, and Farquhar Shaw (1743)

- The official records of the mutiny in the Black Watch (1910)

- The Official Diary of Lieutenant-General Adam Williamson (1912)

- The Black Watch – Story of the “Red Heckle” (electricscotland.com)