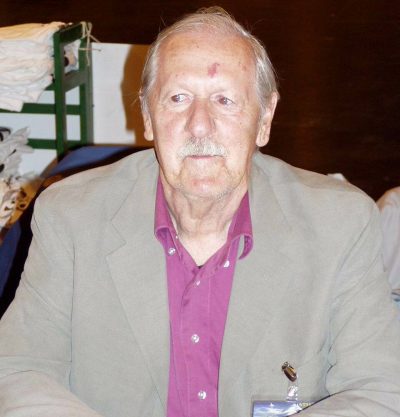

Back in 1987 I met one of the UK’s most prolific science fiction authors when he and the actor Ken Campbell were touring a show called Science Fiction Blues.

] Book Talk [ Rewind ]

Brian Aldiss [

A shadowy form towers in the recess, chuckling demonically like an out-take from a gothic nightmare. I hold my ground. As it lurches forward, a grin wrinkles its cheeks.

“Hello, I’m Brian.” In the light, the eight-foot monster diminishes to an ageing s.f. writer. No bolts through the neck here, just grey swept-back hair and square-rimmed glasses. “It’s rather weird to be a British science-fiction writer: most of them are American, you know,” he confides and then laughs that laugh again.

To most people s.f. is pure fantasy – Spock and Scotty, phasars and photons, teleports and tribbles – all boldly going where no green bug-eyed monster had been before. But Brian Aldiss prefers to bring things back down to earth. “You know when Star Trek first came out the Americans were having an awful lot of trouble in Vietnam. So here was a very consoling fantasy of the Starship Enterprise going round the galaxy sorting out everyone’s problems with a bit of wisdom, a bit of insight and some good old American know-how.”

His own books, he claims, “spring very strongly from whatever’s happening at the time.” At sixteen the Royal Signal Corps in the exotic Far East was “what was happening”. It was, he muses, “not unlike another planet: a lot of the landscapes and people that I met, I’ve transferred into a science-fiction mode.”

“I don’t see a lot of difference between writing an ordinary contemporary novel and writing a science-fiction novel. The feeling’s much the same, you’ve got a story to tell but you may begin from a different direction. I’ve just always thought that science-fiction was more exciting.”

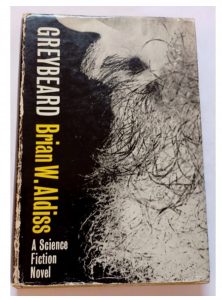

He cites Greybeard, which was published in the sixties as “directly inspired by people saying, `Well you know that nuclear experiments are very dangerous: let’s not do them on earth, let’s do them in space’. As though we weren’t closely related to space. So, there was behind the story a very strong moral feeling.”

The crossover between fantasy and fact fascinates Aldiss. “There certainly is a relationship between science-fiction and eventual reality. It’s a rather complex one, but a lot of things have started off as science-fiction. There’s an argument that says that space-flight wouldn’t have been possible unless it had first been conjured up in our imaginations. I don’t think we would have got to the moon, which I regard as rather a good thing, if it hadn’t been for a lot of dreamers whose ideas were considered to be crazy and unacceptable. It needed a lot of faith in the 1930s to believe that space-flight was going to be possible within one generation.”

It was 1933 when Aldiss wrote his first short story at the ripe-old age of eight and he’s never lost the love of writing, “I try and tell myself a story and if I find I’m bored over a page I’ll screw it up and write another page that isn’t boring. If I bore myself, the most patient of my readers, I’m certainly going to bore everyone else.” That boyish joy of discovery extends throughout his work as he manipulates time and twists evolution. “I’ve always been attracted to the crazy aspect of science-fiction.”

As a parting shot, I ask who’s most influenced him.

“H. G. Wells and,” he chuckles, “Mary Shelley.”

Who else?!

(A version of this article was first published in Event South West.)